My Irish Catholic parents were not people who talked about sex. Ever. My four siblings, as far as I know, had to learn about sex the old-fashioned way–on the streets. My brother told me once that, after he had already been “to the street,” my father took him out for a walk. This alone signaled Important Doings, because my father was not big on walking. The city mailbox was less than one block from our home, and my father used to drive there. Once my dad and Johnnie embarked on this unusual father-son walk, Johnnie could see that my dad was trying to move the conversation in a certain direction. It never happened. Apparently my dad “ran up” on the subject a few times, and then aborted the mission. This unsuccessful attempt at a father-son talk was not exceptional for the times. At least in Irish Catholic families, sex simply wasn’t discussed. Ever. (Even such reticence was a step ahead of the previous generation. When my mother was a child, a boy in her class at Our Lady of Peace School told her what turned out to be the correct facts about how babies are made. Appalled, my mother ran home from school and told her mother what she had learned. Without missing a beat, Mommy Mayme replied, “That’s a dirty lie.” I have no idea when my mother realized that indeed it was not a lie but a Beautiful Truth.

My Irish Catholic parents were not people who talked about sex. Ever. My four siblings, as far as I know, had to learn about sex the old-fashioned way–on the streets. My brother told me once that, after he had already been “to the street,” my father took him out for a walk. This alone signaled Important Doings, because my father was not big on walking. The city mailbox was less than one block from our home, and my father used to drive there. Once my dad and Johnnie embarked on this unusual father-son walk, Johnnie could see that my dad was trying to move the conversation in a certain direction. It never happened. Apparently my dad “ran up” on the subject a few times, and then aborted the mission. This unsuccessful attempt at a father-son talk was not exceptional for the times. At least in Irish Catholic families, sex simply wasn’t discussed. Ever. (Even such reticence was a step ahead of the previous generation. When my mother was a child, a boy in her class at Our Lady of Peace School told her what turned out to be the correct facts about how babies are made. Appalled, my mother ran home from school and told her mother what she had learned. Without missing a beat, Mommy Mayme replied, “That’s a dirty lie.” I have no idea when my mother realized that indeed it was not a lie but a Beautiful Truth.

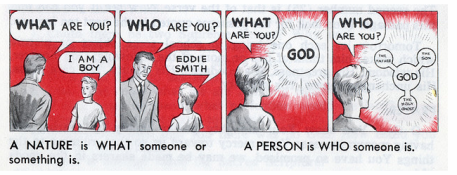

By the time I started in the direction of puberty in the late 1960’s, parents were encouraged—even admonished—to tell their children about sex; learning about it on the streets was no longer acceptable. The sixth grade teachers at Christ King School must have, at some point, informed our parents that we would be talking about sex in Religion class and to be prepared for questions. I think this must be so because one day out of the blue my mother asked me to bring my Religion Textbook home with me. She wanted to look at it. This was an unprecedented and surprising request. Until that moment, I had no real sense that my parents even knew exactly what classes I was taking, much less what books we were reading. Nonetheless, I dutifully complied.

My mother took the textbook from me and took a quick glance at the Table of Contents, then turned to a specific page and read something there. Then she closed the book and handed it back to me, saying “Well, that’s fine.” Deeply intrigued and ever on the alert for Odd Parental Behavior, I noted as best I could where in the book she had looked, and as soon as I had the book back in my possession, I went there.

I found the pertinent paragraphs. It was a section of our book we had not read yet, and it was called God, Sex and You. It was mystifying. Our author started out by telling us that sex is Very Beautiful. Then he said that sex is like a fire. If I put logs into my fireplace and light them on fire, they give the room a lovely glow and lend warmth to all who are gathered. That is, the author pointed out, a Good Fire. A Bad Fire is when, instead of putting logs in the fireplace and lighting a match, I set fire to my whole house. Such a fire rages out of control quickly and destroys everything in its path. That, the author pointed out, is a Bad Fire. He concluded by saying that sex should always be like the Good Fire and not like the Bad Fire.

I had no idea what they were talking about, and why anyone thought he needed to tell me not to set my own house on fire. I may not have been an “A” student at the time, but I knew not to do that. I didn’t pursue the matter further, though; by that time, I was resigned to the basic strangeness of all adults whenever the word “sex” was spoken.

By the time we actually arrived at this part of the textbook in Religion class, I had a  better—though by no means clear—idea of what they were getting at, because my mother had done her maternal duty and taken me to a movie at Christ King School about the Facts of Life.

better—though by no means clear—idea of what they were getting at, because my mother had done her maternal duty and taken me to a movie at Christ King School about the Facts of Life.

I do not know the name or provenance of the movie they showed; all sixth grade parents were encouraged to attend along with their child. There were actually two movies, because the boys and their parents were sent to the “big gym” and the girls and their parents were directed to the “small gym.” My father did not go with us, so it was just my mother and me taking our seats while one of the sixth grade teachers welcomed us. I don’t know if the boys and the girls were shown the same film, but I doubt it. Our film involved a lot of information that I realize, in retrospect, would never have been deemed suitable for the boys.

I have only very dim memories of the film, but three things stayed with me: first, it opened with scenes from the Garden of Eden; we saw Adam and Eve looking happy and healthy, and then God pointing out a few trees that were Strictly Off Limits, and then the snake showed up and things spiraled downward from there. It was a familiar story. The one scene from this part of the film that I remember vividly was the moment when Adam and Eve were kicked out of the Garden. There they stood, with their hair and/or hands strategically covering their private parts, looking extremely sad. Behind them a very angry angel glared in their direction and slid a golden spear through the handles of the Gates of Paradise, shutting them out for good.

Having heard this story many times, both at Christ King School and at mass, I admit that my mind started to wander at this point. We had had to leave the house immediately after dinner to make it to the film on time, and so dessert had not been served. I knew there was some butter pecan ice cream in the freezer and some Hershey’s Syrup in the fridge. I was musing on this pleasant prospect when I realized that the film had exited Genesis and was now showing scenes of Typical Young People Doing Fun Young People Things. I was not a typical young person, though I often longed to be, and my ideas of fun almost never meshed with what other young people did, so whenever I was offered a peek into scenes from a typical life, I soaked them up with the passion of an anthropologist.

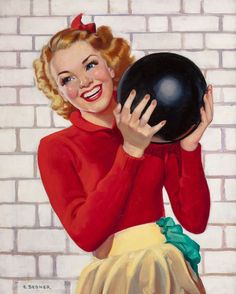

The Typical Fun Girls in this movie were, at first, having milkshakes together at an ice cream store (very nearly derailing my focus back to that butter pecan ice cream awaiting me at home), and then they all went bowling together. Over the pictures of these smiling, happy young women, the narrator intoned the information that “something was going to happen to me.” Soon. Now they had my attention. What was going to happen to me?

The Typical Fun Girls in this movie were, at first, having milkshakes together at an ice cream store (very nearly derailing my focus back to that butter pecan ice cream awaiting me at home), and then they all went bowling together. Over the pictures of these smiling, happy young women, the narrator intoned the information that “something was going to happen to me.” Soon. Now they had my attention. What was going to happen to me?

I am pretty sure I paid close attention at that point but I surely must have missed some crucial bit of information, because now the narrator was telling us that as a result of this thing that was going to happen, there would be times during the month when I would feel lethargic and even cranky. At those times, I would not want to go bowling with the gang. However, the narrator encouraged me, I should go bowling nonetheless; it was very important that I bowl, no matter how I felt.

This seemed to me to be a very badly made movie. I had no idea why we moved from Adam and Eve to this bowling scenario. We were still years away from Rotten Tomatoes back in 1969, but this film would have scored abysmally on my Tomatometer. After the exhortation about bowling, there were some diagrams of what looked like part of the engine of my father’s car—tubes and knobs and a central joining-up place—that the narrator said was my Female Reproductive System. He went on to say that God was amazing, because He had thought so far into my future that I already had all my eggs. “Just think of it!” said the Narrator. “Right now, this very day, you have all of your eggs already in your body!”

I cannot adequately describe how confused I was by this. All my eggs already inside me? I thought. But I eat eggs. Eggs that are clearly outside me and then I eat them and only then are they inside me. They are never “already there.” Should I not be eating extra eggs, since I already have the eggs I need right there inside me? Before I could ponder this weird Narrator Side Trip, however, the lights came up. The movie was over.

On the way home from Christ King School that night, my mother asked me if I understood the film. “Yes,” I replied honestly. I thought I did understand it; I just didn’t think it was very good. I hadn’t been asked for an evaluation, so I didn’t tell her that I had found the movie confusing and not at all well-made. Genesis? Bowling? Eggs? Then my mother asked if I had any questions. I could tell that she hoped that I didn’t, so I did not ask any, but I certainly had some. For starters, I had only been bowling once in my life, and I hated it. I was also terrible at it. Why was it now important that I embrace bowling with my friends? And why was bowling important only at certain times of the month, when I was cranky and out of sorts? Why did we go to school at night just to brush up on the well-known facts of Genesis? And what was the mysterious thing that was going to happen to me? And what was the deal with the eggs?

A few months after the Really Bad Movie about Adam and Eve, Bowling, and Eggs, I read an article in the Milwaukee Journal about a sexual assault. I didn’t know what the phrase “sexual assault” meant, so I asked my mother. She said it was an assault having to do with sex. Well, that was not at all helpful, so I asked her what “sex” was. My brother Johnnie was in the room during this conversation, and he began to chuckle. That was my clue that something was up; I had a clear vibe that information was being withheld.

My mother said that “sex” meant the female sex was a girl and the male sex was a boy. Johnnie’s chuckling intensified, and he said to my mother, “Good one.” Now I was really hot on the scent. They were both holding out on me. At that moment, my mother decided it was time to start making dinner, so she left for the kitchen to assemble grilled cheese sandwiches. I followed her.

I was a child flawed in many ways, but I had some strengths. One of them was doggednss. There was unstated information between Johnnie and my mom, and I was determined to get to the bottom of it. I stood sentinel at the cutting board while my mother methodically placed slices of Kraft American Cheese on individual slices of bread and topped them with tomato, green pepper and onions. I pushed and pushed for the information I wasn’t getting, and finally my mother erupted with, “Ok! Sex is what happens when the penis is inserted into the vagina!” As my mother continued slapping sandwiches together, I felt as if actual dawn were breaking over my consciousness; it was one of the few moments in my life when I felt literally enlightened. “That’s why husbands and wives sleep in the same bed!” I crowed. My mother agreed that yes, that was so, but even then I could see that she thought it an odd response. She must also have been confused as to why this was such news to me; after all, she had done her due diligence: she taken me to the film at school and she had even asked if I had had any questions.

At some point I made the connection between my mother’s startling fact about intercourse and that time of the month when I would feel cranky and out of sorts. Unlike a lot of girls my age, I was eager for that part of puberty to begin. Everyone told me that it would mark the beginning of My Life as a Woman, and I was ready. Childhood had not held many charms for me, and I was ready to move on.

I kept careful watch for what my mother told me was called “My Period.” No one told me that when that rite of passage was on the near horizon, my body would change in some other startling ways. Thus it was an unhappy surprise when I went to bed one night and realized that my chest has taken on a disturbing life of its own. I didn’t have breasts, but out of nowhere my nipples were starting to swell up. That can’t be good, I thought to myself, and figured I just might be getting cancer. The thought of asking my mother any more questions in this area was not appealing, so I took matters into my own hands, and tried to pop them with a safety pin.

That did not go well. In fact, it hurt. A lot. Still not in the mood to approach my mother, I told my sister Susan I might be dying, and showed her my chest. Susan studied my chest sagely, then said, “You don’t have cancer. And stop stabbing yourself in the chest. It’s weird. It’s all just part of the whole thing that happens when you get your period. And you can’t stop it.”

I asked her if she had already “become a woman.” “Oh yeah,” she said. “For a few years now.” This was fascinating information for me, as I shared a room with Susan and thought I knew all of her secrets. “Did you know all the facts of life when it happened?” I asked her. “Oh no,” she said casually. “It just came one night when Mom and Dad were out. I thought I was dying of cancer. But I wasn’t. Mom explained when she got home. Then she washed my pajamas.”

Not too long after that conversation, my period arrived. I was so happy. I was a woman. I told my mother and showed her the tiny stain in my underpants. She was prepared, and brought me into her bedroom, opened her chest of drawers, and pulled out a box. In the box were padded things, which she then pinned to a belt she also took out of the box. This was a “sanitary napkin.” I had never seen anything like it. She showed me how to put the belt on, how to pin the pad to the belt, how to pull my underpants up and over this bulky new situation in my swimsuit area. While I was thrilled to be a woman, I found all of these mechanics distasteful and embarrassing. My mother showed me how to wrap a used pad in lots of toilet paper and dispose of it in the wastebasket.

I was not a fan of the mechanics of Becoming a Woman, and by this time, I was eager for the conversation to end. I had no idea how I was expected to live my normal life and still deal with this belt and pin and pad and toilet paper chores. I found out that, in fact, there were now going to be days when I would not be able to go swimming or take a bath. The filmmakers who had been so obsessed with my bowling commitments might have at least mentioned this, I thought. I actually liked swimming and I loved baths. So far I was hearing nothing pleasant about this great moment when I Became a Woman.

And then I heard some magical words. “When you are at this time of the month,” my mother told me, “You aren’t expected to participate in gym class.” Now there was some good news. I despised gym class for many good reasons. “How do I get out of it? I asked her. “Tell the gym teacher at the start of class that you are having your time of the month,” she told me. I can do that, I thought. I can definitely do that. This news almost offset the creepy parts with the belt and the pins and the no swimming rule.

At my very first opportunity, I told Mr. Landisch, our gym teacher, that I could not participate in gym class because it was my time of the month. Instantly uncomfortable, he nodded and mumbled something and hurried off, clipboard in hand. It was as if I had been given a magical incantation. While my classmates climbed ropes and raced each other on tiny little scooters and picked teams for indoor soccer, I happily sat on the sidelines with my book. As time went on, of course, I could not resist using my Get Out of Gym Free card even when it wasn’t officially required. After a few months of that, though, even Mr. Landisch was not fooled. I used my card one morning, but on that particular day, he bellowed at me across the entire gym, “Maloney, you’ve had your period three weeks in a row!” That was the end of that; I knew I could only use my ironclad excuse once a month. It was still better than nothing.

And as for bowling—I didn’t bowl again for at least twenty years. I was still terrible at it. But I felt just fine.

Skipper was a big hit in Barbie World, and so it wasn’t long before Mattel introduced yet another sister, this one named Tutti. Tutti was adorable, and of course I wanted her very badly. My mother thought that Barbie, Ken and Skipper were more than sufficient for my needs, and I despaired of receiving a Tutti doll anytime soon. Luckily for me, however, a birthmark on my neck starting to morph into something ominous right around that very time, and I had to go to the hospital to have it removed. That hospital visit turned out to be my ticket to a Tutti doll.

Skipper was a big hit in Barbie World, and so it wasn’t long before Mattel introduced yet another sister, this one named Tutti. Tutti was adorable, and of course I wanted her very badly. My mother thought that Barbie, Ken and Skipper were more than sufficient for my needs, and I despaired of receiving a Tutti doll anytime soon. Luckily for me, however, a birthmark on my neck starting to morph into something ominous right around that very time, and I had to go to the hospital to have it removed. That hospital visit turned out to be my ticket to a Tutti doll.

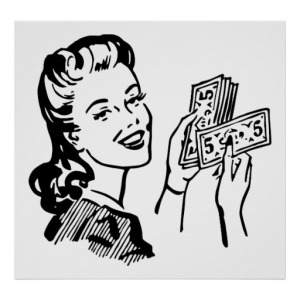

scale-managing system to create this faux ten pound weight loss about thirty days into our agreement. On the appointed day, I turned the scale back to negative ten and announced my ten pound “weight loss.” My mother seemed disappointed that I looked no different, and none of my clothes fit any better, but a deal was a deal and she trusted me. She gave me the money to buy my Francie, and I did; I bought a brunette Francie whom I adored every bit as much as I thought I would. Francie became the ingénue in all my stories, and Bubble Cut Barbie was relegated to the role of wise-cracking older sister. My mother never asked if I was regaining the weight, and she never challenged my claim to have lost it. It was, however, her last attempt to bribe me into going on a diet.

scale-managing system to create this faux ten pound weight loss about thirty days into our agreement. On the appointed day, I turned the scale back to negative ten and announced my ten pound “weight loss.” My mother seemed disappointed that I looked no different, and none of my clothes fit any better, but a deal was a deal and she trusted me. She gave me the money to buy my Francie, and I did; I bought a brunette Francie whom I adored every bit as much as I thought I would. Francie became the ingénue in all my stories, and Bubble Cut Barbie was relegated to the role of wise-cracking older sister. My mother never asked if I was regaining the weight, and she never challenged my claim to have lost it. It was, however, her last attempt to bribe me into going on a diet.

Sitting on the floor, surrounded by the dolls I was sending to their final rest, I was suddenly struck by a lightning bolt. “I could be a writer.” I stopped dead in the middle of my sad chore and gazed down at my dolls, now wrapped in their tissue-paper burial clothes. I could, I realized, still make up stories, still imagine alternate worlds. Instead of acting out those tales with my dolls, I could write them down. If I wrote the stories down, they wouldn’t be tall tales any more, or the lies for which I used to get punished on a regular basis. With utter clarity, I saw my future. Barbie had been my Muse for many years, and my love for her caused me to sin and even to enter a life of crime. I could redeem my criminal past—and survive my actual life—by bringing my Barbie stories inside my head and writing them down. I would grow up and become a writer.

Sitting on the floor, surrounded by the dolls I was sending to their final rest, I was suddenly struck by a lightning bolt. “I could be a writer.” I stopped dead in the middle of my sad chore and gazed down at my dolls, now wrapped in their tissue-paper burial clothes. I could, I realized, still make up stories, still imagine alternate worlds. Instead of acting out those tales with my dolls, I could write them down. If I wrote the stories down, they wouldn’t be tall tales any more, or the lies for which I used to get punished on a regular basis. With utter clarity, I saw my future. Barbie had been my Muse for many years, and my love for her caused me to sin and even to enter a life of crime. I could redeem my criminal past—and survive my actual life—by bringing my Barbie stories inside my head and writing them down. I would grow up and become a writer. When I started my studies at Mount Mary College in the Fall of 1976, I was so grateful to be back in an academic environment that I could have kissed the ground beneath the Arches. My summer job at Northwestern Mutual Insurance Company had paid very well, but the best benefit I received was a fervent and unswerving gratitude for the privilege of being back in school.

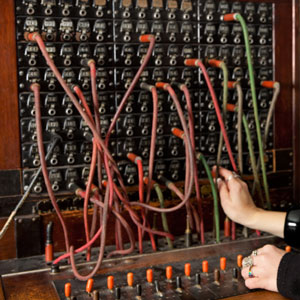

When I started my studies at Mount Mary College in the Fall of 1976, I was so grateful to be back in an academic environment that I could have kissed the ground beneath the Arches. My summer job at Northwestern Mutual Insurance Company had paid very well, but the best benefit I received was a fervent and unswerving gratitude for the privilege of being back in school. As the first few months passed, I got better at managing the board. It’s hard to picture now in the days of smartphones and wireless technology, but an old-fashioned switchboard is an an intimidating thing to behold. The Switchboard was a sizeable box covered with holes into which cables were plugged in order to receive calls. The machine would buzz, and my task was to grab a cable, plug it into the proper opening, and speak into my headset. Once the caller identified his need, I then pulled his cable out of the hole it was in and plugged it into the hole he wanted—for example, the business office, the library, or the dining room. If the call was a personal call for one of the nuns, I had to hold the caller in his spot while I “rang for” the desired nun.

As the first few months passed, I got better at managing the board. It’s hard to picture now in the days of smartphones and wireless technology, but an old-fashioned switchboard is an an intimidating thing to behold. The Switchboard was a sizeable box covered with holes into which cables were plugged in order to receive calls. The machine would buzz, and my task was to grab a cable, plug it into the proper opening, and speak into my headset. Once the caller identified his need, I then pulled his cable out of the hole it was in and plugged it into the hole he wanted—for example, the business office, the library, or the dining room. If the call was a personal call for one of the nuns, I had to hold the caller in his spot while I “rang for” the desired nun. One afternoon, a bevy of nuns visiting from the Mankato, Minnesota Motherhouse landed at Mitchell Field, the main airport serving Milwaukee. Their leader phoned Mount Mary (from a pay phone in a public phone booth) for directions to our campus; her call was answered by me. I have such a poor sense of direction that I have been known to get lost going from one building to the next, and when I took my Driver’s License Exam, I had to put a big blue ring on my left hand so that when the Instructor said, “Turn left,” I would know which way to go.

One afternoon, a bevy of nuns visiting from the Mankato, Minnesota Motherhouse landed at Mitchell Field, the main airport serving Milwaukee. Their leader phoned Mount Mary (from a pay phone in a public phone booth) for directions to our campus; her call was answered by me. I have such a poor sense of direction that I have been known to get lost going from one building to the next, and when I took my Driver’s License Exam, I had to put a big blue ring on my left hand so that when the Instructor said, “Turn left,” I would know which way to go. When the crash happened, I must have made quite a noise, first hitting the car and then hitting the pavement, because people ran out from their houses and businesses on the street and started yelling a lot. Someone threw a blanket on me and somewhere in there I got my breath back, which turned out to mean (a) I was not going to die right then and (b) I was in a great deal of pain. There there were sirens, and an ambulance, and a trip to the hospital that I barely remember. I was very much alive, but I had a rather seriously banged up leg, and would need bedrest, then a leg brace for several months, and rehab for my knee.

When the crash happened, I must have made quite a noise, first hitting the car and then hitting the pavement, because people ran out from their houses and businesses on the street and started yelling a lot. Someone threw a blanket on me and somewhere in there I got my breath back, which turned out to mean (a) I was not going to die right then and (b) I was in a great deal of pain. There there were sirens, and an ambulance, and a trip to the hospital that I barely remember. I was very much alive, but I had a rather seriously banged up leg, and would need bedrest, then a leg brace for several months, and rehab for my knee. they eventually offered a settlement. In order to assess lost wages, my brother had to call Sr. Gertrude Mary and ask for an estimate of those wages. Dear Sr. Gertrude Mary made a very generous estimate of how many hours I would have worked—especially considering that Sr. Joselma wanted me summarily fired that very day—and the money from that accident paid my share of my entire second and third year tuition at Mount Mary College. My knee hurt a lot, the brace was uncomfortable, and rehab was no fun at all, but I was nonetheless pretty happy about the way things turned out. Getting hit by a car was more fun than any job I had ever had, and a leg brace was a small price to pay for getting at least two of my summers back.

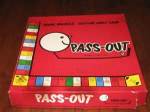

they eventually offered a settlement. In order to assess lost wages, my brother had to call Sr. Gertrude Mary and ask for an estimate of those wages. Dear Sr. Gertrude Mary made a very generous estimate of how many hours I would have worked—especially considering that Sr. Joselma wanted me summarily fired that very day—and the money from that accident paid my share of my entire second and third year tuition at Mount Mary College. My knee hurt a lot, the brace was uncomfortable, and rehab was no fun at all, but I was nonetheless pretty happy about the way things turned out. Getting hit by a car was more fun than any job I had ever had, and a leg brace was a small price to pay for getting at least two of my summers back. command until someone—you guessed it—passed out, and even a black market telephone. When I was young, it was against the law to own one’s own telephone, and woe betide to anyone who dared. The Telephone Company owned all the phones, and that was that. If you wanted a phone or if you moved to a new place, you petitioned the Phone Czar to grace you with one of her telephones, and if fortune smiled upon you, she would let you rent one.

command until someone—you guessed it—passed out, and even a black market telephone. When I was young, it was against the law to own one’s own telephone, and woe betide to anyone who dared. The Telephone Company owned all the phones, and that was that. If you wanted a phone or if you moved to a new place, you petitioned the Phone Czar to grace you with one of her telephones, and if fortune smiled upon you, she would let you rent one. Every month, you paid rent on every phone in your house and when you moved, you left the phones. They were never yours. Outlaws like Jesse James or Richard Nixon might steal phones, but no upstanding citizen would dare. The Phone Company was the only game in town, and you risked fines, prison, and—scariest of all—loss of phone privileges if you messed with Ma Bell. I used to feel an actual shiver of fear every time I looked at Johnnie’s contraband phone. It was an old fashioned black model and he had boldly plugged it right into the Telephone Company’s jack in his bedroom. It worked fine, but I felt butterflies every time I used it, imagining G-men bursting through the front door and cuffing me for breaking the United States Telephone Act.

Every month, you paid rent on every phone in your house and when you moved, you left the phones. They were never yours. Outlaws like Jesse James or Richard Nixon might steal phones, but no upstanding citizen would dare. The Phone Company was the only game in town, and you risked fines, prison, and—scariest of all—loss of phone privileges if you messed with Ma Bell. I used to feel an actual shiver of fear every time I looked at Johnnie’s contraband phone. It was an old fashioned black model and he had boldly plugged it right into the Telephone Company’s jack in his bedroom. It worked fine, but I felt butterflies every time I used it, imagining G-men bursting through the front door and cuffing me for breaking the United States Telephone Act. Mary had a very calm expression on her face, and her arms were sort of reaching out toward me, but she was barefoot and standing on a very large and ugly snake. When I first encountered Mary of the Closet, I was fairly young and hadn’t yet digested the whole “serpent in the garden” story, so I had no idea why God’s mother was serenely squishing an angry snake to death with her bare feet. I was used to hearing Mary referred to in our family prayers as “full of grace,” as a “lovely lady dressed in blue,” as a sweet and pure maiden. I didn’t know how to reconcile those descriptions with this snake-killer who was clearly a force to be reckoned with, and who seemed to look at me with an expression that said, “Don’t even think about crossing me. Ask the snake how that turned for him.”

Mary had a very calm expression on her face, and her arms were sort of reaching out toward me, but she was barefoot and standing on a very large and ugly snake. When I first encountered Mary of the Closet, I was fairly young and hadn’t yet digested the whole “serpent in the garden” story, so I had no idea why God’s mother was serenely squishing an angry snake to death with her bare feet. I was used to hearing Mary referred to in our family prayers as “full of grace,” as a “lovely lady dressed in blue,” as a sweet and pure maiden. I didn’t know how to reconcile those descriptions with this snake-killer who was clearly a force to be reckoned with, and who seemed to look at me with an expression that said, “Don’t even think about crossing me. Ask the snake how that turned for him.” Next to Scary Mary rested our family’s one and only set of encyclopedias, a set of volumes called The Book of Knowledge. I am not sure when the Book of Knowledge was published, but I do recall that when I tried to use it to write an essay on the Unification of Italy, which happened in the late nineteenth century, the Book of Knowledge did not have the updated information; inside its pages, Italy was still a collection of territories grouped around the Papal States.

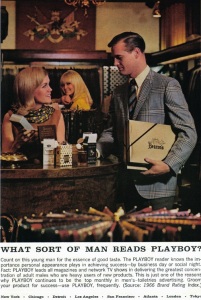

Next to Scary Mary rested our family’s one and only set of encyclopedias, a set of volumes called The Book of Knowledge. I am not sure when the Book of Knowledge was published, but I do recall that when I tried to use it to write an essay on the Unification of Italy, which happened in the late nineteenth century, the Book of Knowledge did not have the updated information; inside its pages, Italy was still a collection of territories grouped around the Papal States. Now of course, I had every intention of retrieving both ice cream and Playboy at the earliest possible date, but as soon as I had secreted the evidence of my crime, I felt weighed down with shame and guilt. I hated thinking about what a terrible person I was: sneaking food I wasn’t supposed to be eating, getting even fatter than I already was, sneaking around in my brother’s room and going through his things, looking at a smutty magazine, which was so awful a deed I couldn’t even imagine confessing it at my next confession (which, I knew, I was now going to have to do) and then hiding the magazine in the gutter.

Now of course, I had every intention of retrieving both ice cream and Playboy at the earliest possible date, but as soon as I had secreted the evidence of my crime, I felt weighed down with shame and guilt. I hated thinking about what a terrible person I was: sneaking food I wasn’t supposed to be eating, getting even fatter than I already was, sneaking around in my brother’s room and going through his things, looking at a smutty magazine, which was so awful a deed I couldn’t even imagine confessing it at my next confession (which, I knew, I was now going to have to do) and then hiding the magazine in the gutter. From that day forward, I was a better, more moral person. I would like to say it was because I saw the light and chose virtue, but the truth is that, after the exquisitely awful experience of discussing hormones with Fr. Heaney, I was a new girl. Whenever I was tempted to do something that I knew was wrong, I thought about how very much I did not want to have to confess it. In the end, then, the one thing I learned from reading Playboy magazine was that sins are really never as exciting in reality as they sound in theory, and they are definitely not worth their cost. Not exactly the “Playboy philosophy,” which in the end is fine with me.

From that day forward, I was a better, more moral person. I would like to say it was because I saw the light and chose virtue, but the truth is that, after the exquisitely awful experience of discussing hormones with Fr. Heaney, I was a new girl. Whenever I was tempted to do something that I knew was wrong, I thought about how very much I did not want to have to confess it. In the end, then, the one thing I learned from reading Playboy magazine was that sins are really never as exciting in reality as they sound in theory, and they are definitely not worth their cost. Not exactly the “Playboy philosophy,” which in the end is fine with me.

My mother worried continuously over my lack of friends and my weight. I loved to read, and I was content to lay on the cot in our basement every day after school and all through the summers with a bag of forbidden chocolate at my side, reading my parents’ collection of Reader’s Digest Condensed Books and whatever else I could find on our shelves. While my mother wished I were less in love with chocolate and would have loved to see me pursuing more physical-fitness oriented activities, she thoroughly understood my love of books. We always shared that passion, and it was a good one to have in common.

My mother worried continuously over my lack of friends and my weight. I loved to read, and I was content to lay on the cot in our basement every day after school and all through the summers with a bag of forbidden chocolate at my side, reading my parents’ collection of Reader’s Digest Condensed Books and whatever else I could find on our shelves. While my mother wished I were less in love with chocolate and would have loved to see me pursuing more physical-fitness oriented activities, she thoroughly understood my love of books. We always shared that passion, and it was a good one to have in common.

She even had a boyfriend, Ned Nickerson. Trouble always found Nancy, but she prevailed in the end, and she didn’t need parents or a boyfriend to do it. Nancy was smart and independent and I loved her.

She even had a boyfriend, Ned Nickerson. Trouble always found Nancy, but she prevailed in the end, and she didn’t need parents or a boyfriend to do it. Nancy was smart and independent and I loved her. I more or less memorized Mrs. Mike, and to this day I recall its images and anecdotes at various moments in my own life. No book quite took over my life, however, the way that Heidi did.

I more or less memorized Mrs. Mike, and to this day I recall its images and anecdotes at various moments in my own life. No book quite took over my life, however, the way that Heidi did. I wanted to be in Heidi’s world, which is odd, since Heidi’s world included being abandoned to live with her grandfather, a very grouchy and distant old man, sleeping in a hut on a desolate mountain with this old man, building a loving connection with that same man through pure resilience and good humor only to be taken away without notice to serve as a companion to a rich crippled girl named Klara whose housekeeper despised Heidi…THIS was the world I wanted to leave my world for? Yes.

I wanted to be in Heidi’s world, which is odd, since Heidi’s world included being abandoned to live with her grandfather, a very grouchy and distant old man, sleeping in a hut on a desolate mountain with this old man, building a loving connection with that same man through pure resilience and good humor only to be taken away without notice to serve as a companion to a rich crippled girl named Klara whose housekeeper despised Heidi…THIS was the world I wanted to leave my world for? Yes. I didn’t realize until many years later that Marjorie had not actually been all that talented, that her own dreams of being an actress and an unconventional woman had been risible given her clear status as a typical Jewish girl of her time.

I didn’t realize until many years later that Marjorie had not actually been all that talented, that her own dreams of being an actress and an unconventional woman had been risible given her clear status as a typical Jewish girl of her time. homework I did turn in that month was not very good. I was doing nothing to improve my solid “D” average in science and math; my reading and spelling scores were good because I didn’t have to study them to excel. Even my reading grade plummeted, though, when I had to turn in an art project about a book I had read. My task was to create a diorama about a book I had enjoyed and, lacking any artistic talent whatsoever, I dressed my Barbie doll in her best dress, put her in a box, and said she was Scarlett O’Hara. I got a D. The diorama next to mine was created by Dianne, a girl I had never seen read an entire book in her life, and she had a scene from Hans Brinker and the Silver Skates, with a pond made from a mirror and realistic looking snow. She got an A.

homework I did turn in that month was not very good. I was doing nothing to improve my solid “D” average in science and math; my reading and spelling scores were good because I didn’t have to study them to excel. Even my reading grade plummeted, though, when I had to turn in an art project about a book I had read. My task was to create a diorama about a book I had enjoyed and, lacking any artistic talent whatsoever, I dressed my Barbie doll in her best dress, put her in a box, and said she was Scarlett O’Hara. I got a D. The diorama next to mine was created by Dianne, a girl I had never seen read an entire book in her life, and she had a scene from Hans Brinker and the Silver Skates, with a pond made from a mirror and realistic looking snow. She got an A. for the train ride to Milwaukee from Chicago. My mother was a bit dubious given the somewhat racy-looking cover, and asked me what it was about. “The airline industry,” I said. “You know, how hard it is to be a stewardess or a pilot.” Reassured, she gave me the money to buy the book, and I read it happily all the way home.

for the train ride to Milwaukee from Chicago. My mother was a bit dubious given the somewhat racy-looking cover, and asked me what it was about. “The airline industry,” I said. “You know, how hard it is to be a stewardess or a pilot.” Reassured, she gave me the money to buy the book, and I read it happily all the way home. I had been in no shape to look through it while I was in the hospital, but I certainly looked forward to perusing it once I got home. One day while she was visiting me, however, my mother started paging through the book while I was napping. I awoke to a very irate mother, who had some rather unfavorable things to say about Jolie. “Who would give such a book to a twelve year old girl?” was, I believe, among them. “The first page I opened to had a picture of two women. Dancing. With each other. And they were both in the nude!” Our Bodies, Ourselves went home that day under my mother’s arm, and in order to read it weeks later, I had to find it on her closet shelf.

I had been in no shape to look through it while I was in the hospital, but I certainly looked forward to perusing it once I got home. One day while she was visiting me, however, my mother started paging through the book while I was napping. I awoke to a very irate mother, who had some rather unfavorable things to say about Jolie. “Who would give such a book to a twelve year old girl?” was, I believe, among them. “The first page I opened to had a picture of two women. Dancing. With each other. And they were both in the nude!” Our Bodies, Ourselves went home that day under my mother’s arm, and in order to read it weeks later, I had to find it on her closet shelf.

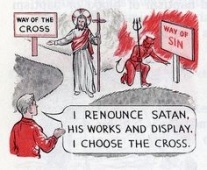

Second grade was the year that we made our First Confession at Christ King School. I was in the second grade in 1966, so the changes wrought by Vatican II were still two years away for us. Sister Shawn Marie and Fr. Lippert did their best to make this process reassuring; Father visited class and practiced the routine with us (“Bless me, Father, for I have sinned. This is my — confession. Here are my sins: —–I am sorry for these and all my sins, especially for all the times I —–.”) Each student was in charge of enumerating her own venial sins, but for some reason that is not clear to me it was decided that Sr. Shawn Marie would supply us with what is called our “principal fault,” or the sin that came after “…especially for all the times I —-.” When it was my turn to sit next to Sister’s desk, I ran through the whole script with her and when I got to the “especially….” part, Sister supplied the words, “….for all the times I was lazy.” I remember thinking, “Huh. Did not see that coming. Lazy. Is that even a sin?”

Second grade was the year that we made our First Confession at Christ King School. I was in the second grade in 1966, so the changes wrought by Vatican II were still two years away for us. Sister Shawn Marie and Fr. Lippert did their best to make this process reassuring; Father visited class and practiced the routine with us (“Bless me, Father, for I have sinned. This is my — confession. Here are my sins: —–I am sorry for these and all my sins, especially for all the times I —–.”) Each student was in charge of enumerating her own venial sins, but for some reason that is not clear to me it was decided that Sr. Shawn Marie would supply us with what is called our “principal fault,” or the sin that came after “…especially for all the times I —-.” When it was my turn to sit next to Sister’s desk, I ran through the whole script with her and when I got to the “especially….” part, Sister supplied the words, “….for all the times I was lazy.” I remember thinking, “Huh. Did not see that coming. Lazy. Is that even a sin?” all those relaxed second graders who had already been there and done that. I sat in the pew and ran through the script in my head, trying to remember the right words and where to plug in my sins. After not nearly enough time had passed, Theresa Buth opened the heavy wooden door of the confessional and nodded at me to enter. I gulped and walked inside the little dark room. Best to just launch in, get it done and exit with as much panache as possible, I decided, so I knelt down and said the whole thing in one big breath: “BlessmefatherforIhavesinnedherearemysins…..” etc. Just as I was finishing up I heard a scrapy, sliding sound in front of my face and suddenly a kind male voice said, “You may begin.” Begin? I had just done the whole thing! Where was HE?” He was, of course, on the other side of the confessional. I closed my eyes in resignation and started over: “BlessmefatherforIhavesinned…” I remembered everything I had planned to say; I did not, however, confess being lazy as my major sin, as Sister had instructed me. I had decided, all on my own, that my Big Sin in the last action-packed seven years was stealing a holographic block from Patty Goodnetter. The block I had stolen was so attractive to me because the pictures kept changing, just like a television set. Not knowing the words “holographic block” at the age of seven, I cut to the chase and confessed to Father that I had stolen a television set.

all those relaxed second graders who had already been there and done that. I sat in the pew and ran through the script in my head, trying to remember the right words and where to plug in my sins. After not nearly enough time had passed, Theresa Buth opened the heavy wooden door of the confessional and nodded at me to enter. I gulped and walked inside the little dark room. Best to just launch in, get it done and exit with as much panache as possible, I decided, so I knelt down and said the whole thing in one big breath: “BlessmefatherforIhavesinnedherearemysins…..” etc. Just as I was finishing up I heard a scrapy, sliding sound in front of my face and suddenly a kind male voice said, “You may begin.” Begin? I had just done the whole thing! Where was HE?” He was, of course, on the other side of the confessional. I closed my eyes in resignation and started over: “BlessmefatherforIhavesinned…” I remembered everything I had planned to say; I did not, however, confess being lazy as my major sin, as Sister had instructed me. I had decided, all on my own, that my Big Sin in the last action-packed seven years was stealing a holographic block from Patty Goodnetter. The block I had stolen was so attractive to me because the pictures kept changing, just like a television set. Not knowing the words “holographic block” at the age of seven, I cut to the chase and confessed to Father that I had stolen a television set.