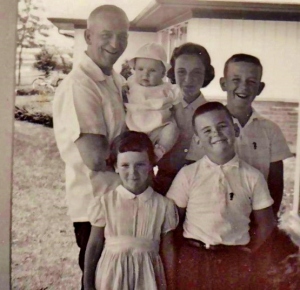

I grew up in an Irish Catholic family. For some reason, my non-Catholic, non-Irish friends always assume that my childhood must have involved lots of family rosaries, miraculous medals and novenas. Invariably, these friends picture us crossing ourselves compulsively, tossing holy water around with abandon and building shrines to the Blessed Mother in every corner of our home.

It wasn’t like that. We did have a large (and intimidating) statue of Mary in my brother’s bedroom closet (for more about her, click here). There was a sizeable statue of the Infant Jesus of Prague in the niche halfway up our stairs. Rosaries did show up in just about every nightstand drawer. My mother did say novenas. So yes, Catholicism was pretty clearly the center of our family life—we went to mass together as a family every Sunday, attended Catholic schools, were expected to keep track of our sins and go to confession when it was necessary— but we were never a demonstrative family when it came to religious practices. My mother and father both prayed on their knees at the side of their bed every night before they retired, but they never asked to pray with us, and they never talked much to us about their personal relationship with Jesus. Religion was treated like sex in my family—a good thing, clearly necessary to family life, but a bit awkward and definitely not to be discussed in public.

One family prayer we did endorse was grace before meals; that we said together every night without fail. We didn’t just say the “Bless us, O Lord,” part like everyone else I knew. We started out with words I found out much later in life come from Evening Prayer in the Roman Breviary: “Visit we beseech thee, O Lord, this house and family, and drive far from us the snares of the Enemy. May Thy holy angels dwell herein; may they keep us in peace, and may Thy blessing be always upon us.” My grandmother Mimi had used this prayer as grace before meals when my father was growing up, and he carried that tradition forward into his own family.

I never gave much thought to these words when I was a child saying them, but it didn’t matter. My parents believed that the Church was right to insist on the value of rote prayer, and that was that. We didn’t say grace every night because we were on fire with the Holy Spirit, or filled with passion for Jesus. We said grace every night because that is what we did. No one cared how we felt. Our feelings weren’t the point. Honoring God was the point.

There were nights when my father would come to the table and be very cross, no doubt after a hard day at the office. There were nights when my mother was preoccupied and tired. There were nights when grace was a hurried muttering, when the Sign of the Cross looked like we were “brushing off flies” as my mother used to say. There were nights when we would barely have breathed the final “amen” before we five children were bickering over who took the biggest helping of meat.

When my maternal grandmother visited us for dinner, she would sometimes point out that it hardly seemed useful to say grace at all, given how rude, uncharitable and begrudging we often were immediately afterward. She was right to point out the all-too-wide discrepancy between our words and our post-grace activities. Those  “Holy Angels,” rather than dwelling at our table some nights, would have no doubt preferred to run for their lives. As a child, I secretly agreed with my grandmother. But my parents didn’t think that prayer was meaningful because of the feelings we have about it; words are powerful in themselves. If we ever doubted it, my father would ask us if we thought that a bridegroom was ever released from the marital vows he spoke out loud because he “wasn’t really feeling them.” We kept right on saying grace.

“Holy Angels,” rather than dwelling at our table some nights, would have no doubt preferred to run for their lives. As a child, I secretly agreed with my grandmother. But my parents didn’t think that prayer was meaningful because of the feelings we have about it; words are powerful in themselves. If we ever doubted it, my father would ask us if we thought that a bridegroom was ever released from the marital vows he spoke out loud because he “wasn’t really feeling them.” We kept right on saying grace.

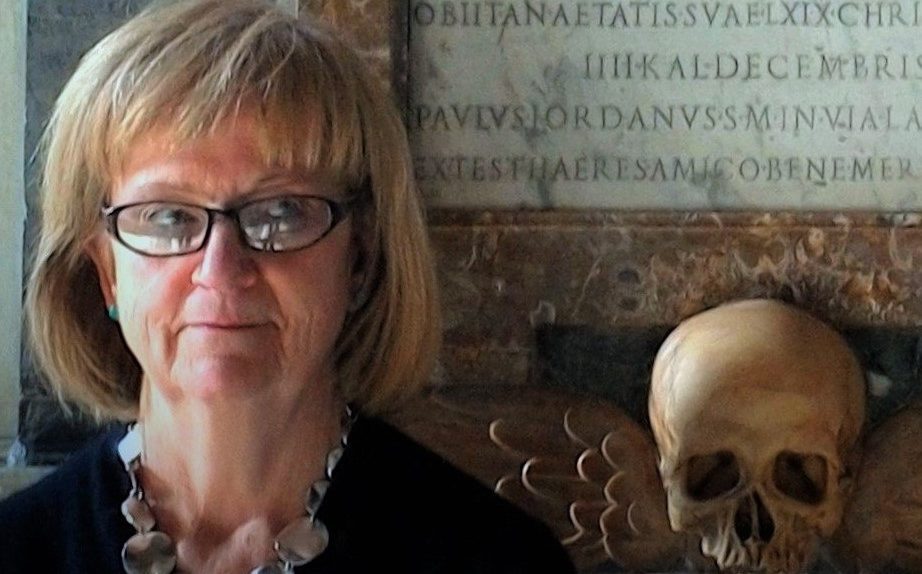

After I grew up and got married, my husband and I fell out of the habit of saying grace at all. Then our first child was born, and I started to think more about prayer; being a mother was an excellent way to learn the lesson that, like love, prayer is an action, not a feeling. I often got up in the middle of the night to comfort or feed my sobbing baby, even though I had to teach a class on Kant the next morning at 8 a.m. The baby didn’t care how I felt. He just wanted me to show up, preferably with a bottle. To him, showing up was love. And he was right. As my children grew up, I saw this truth even more clearly. When my daughter would ask me, “Mommy, do you want to play Candyland with me?” I would think, “Hmmm; I would rather stick a fork in my eye,” but I would say, “Sure.” If I had waited until I felt so much love flowing through me that I wanted to play Candyland, well, Cate would still be sitting on her side of the board, waiting for me. In the same way, my parents insisted that we say the words of our grace every single night regardless of how we felt, or what we actually wanted to be doing. That was the one prayer we said together as a family, even on nights when we didn’t particularly want to be in that family.

In March of 1997, my father was diagnosed with inoperable lung cancer; he died just five months later on August Sixth, the feast of the Transfiguration. Ten days before he died, we celebrated his 77th birthday. He was very ill; it was a struggle for him just to sit in his chair at the head of the table, but it was his birthday, he was a stubborn Irishman, and he did it.

My mother cooked a pork roast—he loved the gravy from a good pork roast, and the browned potatoes–and my sisters and brothers and our spouses gathered in our dining room to be together at the dinner table for what we all knew would be the last time.

I will always remember that night. My father summoned every ounce of energy and strength he had left to celebrate at that meal with us. We laughed a lot; we shared memories, and my father was even able to eat a bit. But what I will never forget is the moment we all sat down at the table to eat. There was the briefest moment of silence, and then my mother, my father and we five Original Maloneys, joined by our spouses, began to say the grace that we had said for over fifty years as a family. That grace, prayed every night of my childhood, sometimes devoutly, sometimes distractedly, sometimes with love, sometimes with annoyance, was prayed on that night with sorrow, joy, gratitude and love; when we beseeched the Lord to visit this house and family, we meant it. When we asked those Holy Angels to keep us in peace, and to bless us always, we meant it.

The prayer we needed was there for us, and we said it together for the last time as a complete family. My brothers are taciturn fellows, and make it their policy not to hug, not to “share,” and certainly not to pray spontaneously in public. Because of who they were, who we were, saying grace together at our last meal with my father was and will forever be the only time I prayed for my father along with my brothers.

The prayer we needed was there for us, and we said it together for the last time as a complete family. My brothers are taciturn fellows, and make it their policy not to hug, not to “share,” and certainly not to pray spontaneously in public. Because of who they were, who we were, saying grace together at our last meal with my father was and will forever be the only time I prayed for my father along with my brothers.

I am grateful that my parents (and the Church) insisted that even rote prayer has value. As a child, I thought it would be better to wait for a deep emotional moment before praying. Now I understand that if I wait for the “right moment” to pray, that moment will likely never come, or come rarely. Saying grace together as a family every night wasn’t a lot, but it was enough, because our habit insured that the prayer would be there when we needed it most.

Just twelve days after that birthday dinner, we went with my mother to the funeral home to make the final arrangements for my father’s wake and funeral. One of our tasks was to choose a prayer for the back of my father’s holy card. My father had never expressed a preference, and we couldn’t decide what sort of prayer he would have wanted. Then my brother Johnnie sat forward and said, very quietly, “I have a suggestion. I think it should be our grace.” The moment he said it, we all knew he was right, and that is the prayer we used.

We didn’t always live up to the prayer we said every night at our dinner table, and we  didn’t always pay enough attention to what we were saying. But because of that daily prayer, I will carry with me always the memory of my father sitting at the head of our dinner table one last time, praying with and for the family he loved. Those “Holy Angels” did indeed show up for us, just as we had been asking them to, every night. They didn’t wait for us to have the proper emotions. They just needed us to ask—and for fifty years, we did.

didn’t always pay enough attention to what we were saying. But because of that daily prayer, I will carry with me always the memory of my father sitting at the head of our dinner table one last time, praying with and for the family he loved. Those “Holy Angels” did indeed show up for us, just as we had been asking them to, every night. They didn’t wait for us to have the proper emotions. They just needed us to ask—and for fifty years, we did.

This is such a powerful entry in your blog; I am at a loss for words (which is rare). Thank you so much for sharing this – I wish I could express how much personal meaning I’ve found here and how much it moved me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautiful, sad, and hopeful. Good, good story, Anne.

LikeLike